Reproductive system in sheeps and goats

Reproductive system in sheeps and goats

- Female reproductive system

- Male reproductive system

- Effect of temperature on reproduction

- Factors affecting puberty

- The estrus cycle in ewes and does

- Measures of reproductive performance

- Age at puberty

- Age at first lambing/kidding

- Parturition interval (Lambing/kidding interval)

- Fertility

- Litter size (LS)

- Seasonality of breeding

Female reproductive system

The reproductive tract of ewes and does is similar. The female reproductive tract consists of the vulva labia, vagina (copulatory organ), cervix, body of the uterus, uterine horns, oviduct (also called Fallopian tube) and the ovary.

- Ovaries : The ovaries contain the ova (eggs), and secrete female reproductive hormones (progesterone and estrogens).

- Oviduct : The oviduct opens like a funnel (the infundibulum) near the ovary. The infundibulum receives ova released from the ovary and transports them to the site of fertilization in the oviduct. The oviduct is involved in sperm transport to the site of fertilization, provides a proper environment for ova and sperm fertilization, and transports the subsequent embryo to the uterus.

- Uterus : The uterus consists of two separate horns (coruna). In animals with multiple births, each horn can contain one or more fetuses. The uterus provides a proper environment for embryo development, supports development of the fetus (supplying nutrients, removing waste, and protecting the fetus), and transports the fetus out of the maternal body during birth.

- Cervix : The cervix is the gateway to the uterus and is a muscular canal consisting of several folds of tissue referred to as “rings.” The cervix has relatively little smooth musculature. It participates in sperm transport, and during pregnancy, blocks bacterial invasion. The mucus produced during pregnancy (also during the luteal phase) forms a plug that makes the opening through the cervix impermeable for micro-organisms and spermatozoa.

- Vagina : This is the exterior portion of the female reproductive tract and is the site of semen deposition during natural mating.

- Vulva : barrier for preventing external contamination of the female reproductive tract.

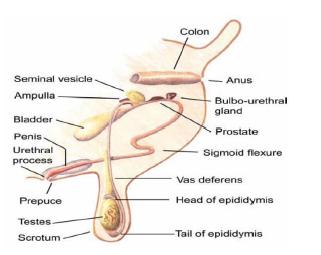

Male reproductive system

The male reproductive system consists of testicles, which produce sperm and sex hormones, a duct system for sperm transport, accessory sex glands, and the penis, or male organ of copulation, which deposits semen in the female.

Male reproductive system

- Testes : The testes are paired organs which descend from the abdominal cavity during fetal development to lie in the scrotum. They produce the male gametes (spermatozoa) and secrete the male sex hormone, testosterone. Testosterone is essential for the development of male characteristics, maintaining normal sexual behavior and sperm production.

- Scrotum : The scrotum is a muscular sac containing the testes. It supports and protects the testes and also plays a major role in temperature regulation. It maintains the temperature 3 to 5 C below body temperature for optimal function.

- Single versus split scrotum : This could be breed-specific as in Somali goats. Some breeders consider the split scrotum as an undesirable trait and select against it. However, the important thing is to check if equalsized testicles are present and sperm production is normal.

- Vas deferens : The vas deferens is the duct that rises from the tail of the epididymis into the abdomen, where it joins the urethra at the neck of the bladder. It is often referred to as the ‘spermatic cord.’ Removal of a section of the vas deferens in each testis is known as a vasectomy, preventing passage of sperm from the epididymis.

- Accessory sex glands : The accessory sex glands include the bulbo-urethral, prostate, and seminal vesicle glands and the ampulla. Accessory glands secrete additional fluids, which when combined with the sperm and other secretions from the epididymis, form the semen. Some of the secretions contain nutrients like fructose while others produce alkali secretion to raise the pH of the ejaculate. These secretions are added quickly and forcibly during the mating to propel sperm into the urethra.

- Penis : This is the final part of the male reproductive tract and its function is to deposit semen into the vaginal tract of the female. At the end of the penis is a narrow tube called the urethral process (or ‘worm') that sprays the semen in and around the cervix of the ewe/doe. The preputial sheath protects the penis, except during mating.

Scrotum types - Single scrotum Partially split scrotum Split scrotum

Effect of temperature on reproduction

- Increased body temperature can lower the reproductive rate in ewes/does by decreasing ovulation rate, delaying heat cycles or by increasing embryonic mortality.

- Heat stress in males affects the process of spermatogenesis and can render bucks and rams temporarily sterile for 6 to 10 weeks.

- For these reasons, it is important to assist animals in maintaining body temperature, especially during times of the year when ambient temperature is high.

- A simple provision of shade in range production systems could reduce the negative effect of heat.

- Physiological mechanisms in the male assist in regulating temperature.

Factors affecting puberty

- Several factors that are known to influence the age at puberty are as follows

- Nutrition

- Body weight

- Breed

- Season of birth

- Growth rate

- Nutrition is among the most significant factors influencing reproductive development and the onset of puberty.

The estrus cycle in ewes and does

Once puberty is reached, large domestic animals such as sheep and goats display a polyestrous (repeated reproductive cycles) pattern of reproductive activity. The estrus cycle, defined as the number of days between two consecutive periods of estrus (heat), is on average 17 days in ewes and 21 days in does.

- The signs of estrus in the ewe are not obvious unless a ram is present.

- As in the doe, the vulva is swollen and redder than usual, and there is a discharge of mucus but is difficult to see in a ewe with a tail or fleece.

- All of the symptoms mentioned may not be exhibited by a doe or ewe in estrus.

- The best confirmation of estrus is when the doe or ewe stands when being mounted. This is commonly called ‘standing heat.’

- The duration of estrus is variable in that it is shorter in younger ewes and does but longer in older animals.

- Normal duration will be 24 to 36 hours.

Measures of reproductive performance

Measures of reproduction commonly used in sheep and goats include age at puberty, age at first lambing/kidding, post-partum interval, parturition interval and fertility indices.

Age at puberty

- It is difficult to have an accurate measure of puberty unless hormonal assays are done at certain intervals (biweekly).

- On experimental stations, puberty may be recorded as the first behavioral estrus observed. This estrus is called pubertal estrus.

- The manifestation is not strong and its duration is short, hence, requiring close attention for heat detection.

Age at first lambing/kidding

- This trait can be recorded easily in a farmer’s flock. There is a big variation among production systems and breeds for this trait (12–24 months). It is usually late in animals living in harsh environments.

- Ewes and does giving birth in the dry season have a longer interval compared to those lambing/kidding during the rainy season.

- Ovarian activity in most tropical breeds commences after weaning. Suckling interferes with hypothalamic release of GnRH, provoking a marked suspension in the pulsatile LH release, resulting in extended postnatal anestrous.

- Females at earlier parities take longer than older ones to return to reproductive status.

Parturition interval (Lambing/kidding interval)

- This refers to the number of days between successive parturitions. It is called lambing interval in ewes and kidding interval in does.

- Under normal circumstances (no drought), tropical sheep/goats should be lambing/kidding at least three times in 2 years. For this to be realized, lambing/kidding interval should not exceed 8 months (245 days).

- As the major component of parturition interval is post-partum interval (PPI), accelerated lambing or kidding revolves around manipulating PPI because a shorter PPI will result in a shorter parturition interval.

- Better nutrition and early weaning could impact this measure of reproductive performance.

- Tests on an eight-month lambing interval under controlled mating in Horro sheep has shown acceptable results in both ewe and lamb performance.

- One of the most important ways of increasing offtake rate is through reduction of the parturition interval and, if done with optimal input, this may help in meeting the growing demand of the export trade.

Fertility

- Various definitions of fertility exist in literature such as conception rate, fecundity, prolificacy, birth rate, etc.

- A general definition of fertility is the number of ewes lambing or does kidding divided by the number of ewes/does mated.

- Fertility is affected by factors such as nutrition, age, diseases and season of mating. In most cases, there is a positive effect of supplementation.

- Supplementation during the mating period (shortly before the mating period and afterwards) could increase the number of ova shed and improve embryo survival.

- This practice is called flushing and is discussed in the nutrition and management sections.

- Age of the ewe or doe is also an important factor.Fertility increases with age, and also starts to decline with old age.

Litter size (LS)

- This is a combination of ovulation rate and embryo survival.

- Litter size (LS) varies between 1.08 and 1.75 with average of 1.38.

- A litter size of 1.93 has been reported in Boer goats. This is said to increase to 2.5 with selection.

- Sheep and goats in the pastoral areas are known to give birth to singles only. This might be due to negative selection that has taken place in the environment.

- Heritability estimates suggest the possibility of genetic improvement in LS through selection.

Seasonality of breeding

- Different sheep and goat breeds have developed in a wide range of environments and have consequently evolved a variety of reproductive strategies to suit these environments.

- Local breeds of sheep and goats in tropical conditions are either non-seasonal breeders or exhibit only a weak seasonality of reproduction.

- Females ovulate and exhibit estrus almost the whole year round, even though short periods of anovulation and anestrous are detected in some females.

- Two main hypotheses can be raised to explain the near-absence of seasonality: either the females are insensitive to photoperiod, or the amplitude of the photoperiodic changes is too small to induce seasonality.

Source : Pashu sakhi Handbook

Last Modified : 7/3/2023